Continuous function

| Topics in Calculus | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental theorem Limits of functions Continuity Mean value theorem

|

In mathematics, a continuous function is a function for which, intuitively, small changes in the input result in small changes in the output. Otherwise, a function is said to be "discontinuous". A continuous function with a continuous inverse function is called "bicontinuous". An intuitive—though imprecise, inexact, and incorrect—idea of continuity is given by the common statement that a continuous function is a function whose graph can be drawn without lifting the chalk from the blackboard.

Continuity of functions is one of the core concepts of topology, which is treated in full generality below. The introductory portion of this article focuses on the special case where the inputs and outputs of functions are real numbers. In addition, this article discusses the definition for the more general case of functions between two metric spaces. In order theory, especially in domain theory, one considers a notion of continuity known as Scott continuity. Other forms of continuity do exist but they are not discussed in this article.

As an example, consider the function h(t) which describes the height of a growing flower at time t. This function is continuous. In fact, there is a dictum of classical physics which states that in nature everything is continuous. By contrast, if M(t) denotes the amount of money in a bank account at time t, then the function jumps whenever money is deposited or withdrawn, so the function M(t) is discontinuous. (However, if one assumes a discrete set as the domain of function M, for instance the set of points of time at 4:00 PM on business days, then M becomes continuous function, as every function whose domain is a discrete subset of reals is.)

Real-valued continuous functions

Historical infinitesimal definition

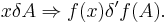

Cauchy defined continuity of a function in the following intuitive terms: an infinitesimal change in the independent variable corresponds to an infinitesimal change of the dependent variable (see Cours d'analyse, page 34).

Definition in terms of limits

Suppose we have a function that maps real numbers to real numbers and whose domain is some interval, like the functions h and M above. Such a function can be represented by a graph in the Cartesian plane; the function is continuous if, roughly speaking, the graph is a single unbroken curve with no "holes" or "jumps".

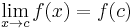

In general, we say that the function f is continuous at some point c of its domain if, and only if, the following holds:

- The limit of f(x) as x approaches c through domain of f does exist and is equal to f(c); in mathematical notation,

. If the point c in the domain of f is not a limit point of the domain, then this condition is vacuously true, since x cannot approach c through values not equal c. Thus, for example, every function whose domain is the set of all integers is continuous.

. If the point c in the domain of f is not a limit point of the domain, then this condition is vacuously true, since x cannot approach c through values not equal c. Thus, for example, every function whose domain is the set of all integers is continuous.

We call a function continuous, if, and only if, it is continuous at every point of its domain. More generally, we say that a function is continuous on some subset of its domain if it is continuous at every point of that subset.

The notation C(Ω) or C0(Ω) is sometimes used to denote the set of all continuous functions with domain Ω. Similarly, C1(Ω) is used to denote the set of differentiable functions whose derivative is continuous, C²(Ω) for the twice-differentiable functions whose second derivative is continuous, and so on (see differentiability class). In the field of computer graphics, these three levels are sometimes called g0 (continuity of position), g1 (continuity of tangency), and g2 (continuity of curvature). The notation C(n, α)(Ω) occurs in the definition of a more subtle concept, that of Hölder continuity.

Weierstrass definition (epsilon-delta) of continuous functions

Without resorting to limits, one can define continuity of real functions as follows.

Again consider a function ƒ that maps a set of real numbers to another set of real numbers, and suppose c is an element of the domain of ƒ. The function ƒ is said to be continuous at the point c if the following holds: For any number ε > 0, however small, there exists some number δ > 0 such that for all x in the domain of ƒ with c − δ < x < c + δ, the value of ƒ(x) satisfies

Alternatively written: Given subsets I, D of R, continuity of ƒ : I → D at c ∈ I means that for every ε > 0 there exists a δ > 0 such that for all x ∈ I,:

A form of this epsilon-delta definition of continuity was first given by Bernard Bolzano in 1817. Preliminary forms of a related definition of the limit were given by Cauchy,[1] though the formal definition and the distinction between pointwise continuity and uniform continuity were first given by Karl Weierstrass.

More intuitively, we can say that if we want to get all the ƒ(x) values to stay in some small neighborhood around ƒ(c), we simply need to choose a small enough neighborhood for the x values around c, and we can do that no matter how small the ƒ(x) neighborhood is; ƒ is then continuous at c.

In modern terms, this is generalized by the definition of continuity of a function with respect to a basis for the topology, here the metric topology.

Heine definition of continuity

The following definition of continuity is due to Heine.

- A real function ƒ is continuous if for any sequence (xn) such that

- it holds that

- (We assume that all the points xn as well as L belong to the domain of ƒ.)

One can say, briefly, that a function is continuous if, and only if, it preserves limits.

Weierstrass's and Heine's definitions of continuity are equivalent on the reals. The usual (easier) proof makes use of the axiom of choice, but in the case of global continuity of real functions it was proved by Wacław Sierpiński that the axiom of choice is not actually needed.[2]

In more general setting of topological spaces, the concept analogous to Heine definition of continuity is called sequential continuity. In general, the condition of sequential continuity is weaker than the analogue of Cauchy continuity, which is just called continuity (see continuity (topology) for details). However, if instead of sequences one uses nets (sets indexed by a directed set, not only the natural numbers), then the resulting concept is equivalent to the general notion of continuity in topology.

Definition using the hyperreals

Non-standard analysis is a way of making Newton-Leibniz-style infinitesimals mathematically rigorous. The real line is augmented by the addition of infinite and infinitesimal numbers to form the hyperreal numbers. In nonstandard analysis, continuity can be defined as follows.

- A function ƒ from the reals to the reals is continuous if its natural extension to the hyperreals has the property that for real x and infinitesimal dx, ƒ(x+dx) − ƒ(x) is infinitesimal.[3]

In other words, an infinitesimal increment of the independent variable corresponds to an infinitesimal change of the dependent variable, giving a modern expression to Augustin-Louis Cauchy's definition of continuity.

Examples

- All polynomial functions are continuous.

- If a function has a domain which is not an interval, the notion of a continuous function as one whose graph you can draw without taking your pencil off the paper is not quite correct. Consider the functions f(x) = 1/x and g(x) = (sin x)/x. Neither function is defined at x = 0, so each has domain R \ {0} of real numbers except 0, and each function is continuous. The question of continuity at x = 0 does not arise, since x is neither in the domain of f nor in the domain of g. The function f cannot be extended to a continuous function whose domain is R, since no matter what value is assigned at 0, the resulting function will not be continuous. On the other hand, since the limit of g at 0 is 1, g can be extended continuously to R by defining its value at 0 to be 1.

- The exponential functions, logarithms, square root function, trigonometric functions and absolute value function are continuous. Rational functions, however, are not necessarily continuous on all of R.

- An example of a rational continuous function is f(x)=1⁄x-2. The question of continuity at x=2 does not arise, since x is not in the domain of f.

- An example of a discontinuous function is the function f defined by f(x) = 1 if x > 0, f(x) = 0 if x ≤ 0. Pick for instance ε = 1⁄2. There is no δ-neighborhood around x = 0 that will force all the f(x) values to be within ε of f(0). Intuitively we can think of this type of discontinuity as a sudden jump in function values.

- Another example of a discontinuous function is the signum or sign function.

- A more complicated example of a discontinuous function is Thomae's function.

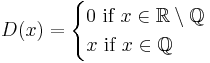

- Dirichlet's function

-

- is continuous at only one point, namely x = 0.

Facts about continuous functions

If two functions f and g are continuous, then f + g, fg, and f/g are continuous. (Note. The only possible points x of discontinuity of f/g are the solutions of the equation g(x) = 0; but then any such x does not belong to the domain of the function f/g. Hence f/g is continuous on its entire domain, or - in other words - is continuous.)

The composition f o g of two continuous functions is continuous.

If a function is differentiable at some point c of its domain, then it is also continuous at c. The converse is not true: a function that is continuous at c need not be differentiable there. Consider for instance the absolute value function at c = 0.

Intermediate value theorem

The intermediate value theorem is an existence theorem, based on the real number property of completeness, and states:

- If the real-valued function f is continuous on the closed interval [a, b] and k is some number between f(a) and f(b), then there is some number c in [a, b] such that f(c) = k.

For example, if a child grows from 1 m to 1.5 m between the ages of two and six years, then, at some time between two and six years of age, the child's height must have been 1.25 m.

As a consequence, if f is continuous on [a, b] and f(a) and f(b) differ in sign, then, at some point c in [a, b], f(c) must equal zero.

Extreme value theorem

The extreme value theorem states that if a function f is defined on a closed interval [a,b] (or any closed and bounded set) and is continuous there, then the function attains its maximum, i.e. there exists c ∈ [a,b] with f(c) ≥ f(x) for all x ∈ [a,b]. The same is true of the minimum of f. These statements are not, in general, true if the function is defined on an open interval (a,b) (or any set that is not both closed and bounded), as, for example, the continuous function f(x) = 1/x, defined on the open interval (0,1), does not attain a maximum, being unbounded above.

Directional continuity

A right continuous function |

A left continuous function |

A function may happen to be continuous in only one direction, either from the "left" or from the "right". A right-continuous function is a function which is continuous at all points when approached from the right. Technically, the formal definition is similar to the definition above for a continuous function but modified as follows:

The function ƒ is said to be right-continuous at the point c if the following holds: For any number ε > 0 however small, there exists some number δ > 0 such that for all x in the domain with c < x < c + δ, the value of ƒ(x) will satisfy

Notice that x must be larger than c, that is on the right of c. If x were also allowed to take values less than c, this would be the definition of continuity. This restriction makes it possible for the function to have a discontinuity at c, but still be right continuous at c, as pictured.

Likewise a left-continuous function is a function which is continuous at all points when approached from the left, that is, c − δ < x < c.

A function is continuous if and only if it is both right-continuous and left-continuous.

Continuous functions between metric spaces

Now consider a function f from one metric space (X, dX) to another metric space (Y, dY). Then f is continuous at the point c in X if for any positive real number ε, there exists a positive real number δ such that all x in X satisfying dX(x, c) < δ will also satisfy dY(f(x), f(c)) < ε.

This can also be formulated in terms of sequences and limits: the function f is continuous at the point c if for every sequence (xn) in X with limit lim xn = c, we have lim f(xn) = f(c). Continuous functions transform limits into limits.

This latter condition can be weakened as follows: f is continuous at the point c if and only if for every convergent sequence (xn) in X with limit c, the sequence (f(xn)) is a Cauchy sequence, and c is in the domain of f. Continuous functions transform convergent sequences into Cauchy sequences.

The set of points at which a function between metric spaces is continuous is a Gδ set – this follows from the ε-δ definition of continuity.

Continuous functions between topological spaces

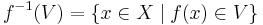

The above definitions of continuous functions can be generalized to functions from one topological space to another in a natural way; a function f : X → Y, where X and Y are topological spaces, is continuous if and only if for every open set V ⊆ Y, the inverse image

is open.

However, this definition is often difficult to use directly. Instead, suppose we have a function f from X to Y, where X, Y are topological spaces. We say f is continuous at x for some x ∈ X if for any neighborhood V of f(x), there is a neighborhood U of x such that f(U) ⊆ V. Although this definition appears complex, the intuition is that no matter how "small" V becomes, we can always find a U containing x that will map inside it. If f is continuous at every x ∈ X, then we simply say f is continuous.

In a metric space, it is equivalent to consider the neighbourhood system of open balls centered at x and f(x) instead of all neighborhoods. This leads to the standard ε-δ definition of a continuous function from real analysis, which says roughly that a function is continuous if all points close to x map to points close to f(x). This only really makes sense in a metric space, however, which has a notion of distance.

Note, however, that if the target space is Hausdorff, it is still true that f is continuous at a if and only if the limit of f as x approaches a is f(a). At an isolated point, every function is continuous.

Definitions

Several equivalent definitions for a topological structure exist and thus there are several equivalent ways to define a continuous function.

Open and closed set definition

The most common notion of continuity in topology defines continuous functions as those functions for which the preimages(or inverse images) of open sets are open. Similar to the open set formulation is the closed set formulation, which says that preimages (or inverse images) of closed sets are closed.

Neighborhood definition

Definitions based on preimages are often difficult to use directly. Instead, suppose we have a function f : X → Y, where X and Y are topological spaces.[4] We say f is continuous at x for some x ∈ X if for any neighborhood V of f(x), there is a neighborhood U of x such that f(U) ⊆ V. Although this definition appears complicated, the intuition is that no matter how "small" V becomes, we can always find a U containing x that will map inside it. If f is continuous at every x ∈ X, then we simply say f is continuous.

In a metric space, it is equivalent to consider the neighbourhood system of open balls centered at x and f(x) instead of all neighborhoods. This leads to the standard δ-ε definition of a continuous function from real analysis, which says roughly that a function is continuous if all points close to x map to points close to f(x). This only really makes sense in a metric space, however, which has a notion of distance.

Note, however, that if the target space is Hausdorff, it is still true that f is continuous at a if and only if the limit of f as x approaches a is f(a). At an isolated point, every function is continuous.

Sequences and nets

In several contexts, the topology of a space is conveniently specified in terms of limit points. In many instances, this is accomplished by specifying when a point is the limit of a sequence, but for some spaces that are too large in some sense, one specifies also when a point is the limit of more general sets of points indexed by a directed set, known as nets. A function is continuous only if it takes limits of sequences to limits of sequences. In the former case, preservation of limits is also sufficient; in the latter, a function may preserve all limits of sequences yet still fail to be continuous, and preservation of nets is a necessary and sufficient condition.

In detail, a function f : X → Y is sequentially continuous if whenever a sequence (xn) in X converges to a limit x, the sequence (f(xn)) converges to f(x). Thus sequentially continuous functions "preserve sequential limits". Every continuous function is sequentially continuous. If X is a first-countable space, then the converse also holds: any function preserving sequential limits is continuous. In particular, if X is a metric space, sequential continuity and continuity are equivalent. For non first-countable spaces, sequential continuity might be strictly weaker than continuity. (The spaces for which the two properties are equivalent are called sequential spaces.) This motivates the consideration of nets instead of sequences in general topological spaces. Continuous functions preserve limits of nets, and in fact this property characterizes continuous functions.

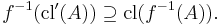

Closure operator definition

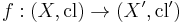

Given two topological spaces (X,cl) and (X ' ,cl ') where cl and cl ' are two closure operators then a function

is continuous if for all subsets A of X

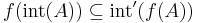

One might therefore suspect that given two topological spaces (X,int) and (X ' ,int ') where int and int ' are two interior operators then a function

is continuous if for all subsets A of X

or perhaps if

however, neither of these conditions is either necessary or sufficient for continuity.

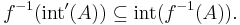

Instead, we must resort to inverse images: given two topological spaces (X,int) and (X ' ,int ') where int and int ' are two interior operators then a function

is continuous if for all subsets A of X '

We can also write that given two topological spaces (X,cl) and (X ' ,cl ') where cl and cl ' are two closure operators then a function

is continuous if for all subsets A of X '

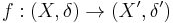

Closeness relation definition

Given two topological spaces (X,δ) and (X' ,δ') where δ and δ' are two closeness relations then a function

is continuous if for all points x and of X and all subsets A of X,

This is another way of writing the closure operator definition.

Useful properties of continuous maps

Some facts about continuous maps between topological spaces:

- If f : X → Y and g : Y → Z are continuous, then so is the composition g ∘ f : X → Z.

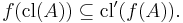

- If f : X → Y is continuous and

- The identity map idX : (X, τ2) → (X, τ1) is continuous if and only if τ1 ⊆ τ2 (see also comparison of topologies).

Other notes

If a set is given the discrete topology, all functions with that space as a domain are continuous. If the domain set is given the indiscrete topology and the range set is at least T0, then the only continuous functions are the constant functions. Conversely, any function whose range is indiscrete is continuous.

Given a set X, a partial ordering can be defined on the possible topologies on X. A continuous function between two topological spaces stays continuous if we strengthen the topology of the domain space or weaken the topology of the codomain space. Thus we can consider the continuity of a given function a topological property, depending only on the topologies of its domain and codomain spaces.

For a function f from a topological space X to a set S, one defines the final topology on S by letting the open sets of S be those subsets A of S for which f−1(A) is open in X. If S has an existing topology, f is continuous with respect to this topology if and only if the existing topology is coarser than the final topology on S. Thus the final topology can be characterized as the finest topology on S which makes f continuous. If f is surjective, this topology is canonically identified with the quotient topology under the equivalence relation defined by f. This construction can be generalized to an arbitrary family of functions X → S.

Dually, for a function f from a set S to a topological space, one defines the initial topology on S by letting the open sets of S be those subsets A of S for which f(A) is open in X. If S has an existing topology, f is continuous with respect to this topology if and only if the existing topology is finer than the initial topology on S. Thus the initial topology can be characterized as the coarsest topology on S which makes f continuous. If f is injective, this topology is canonically identified with the subspace topology of S, viewed as a subset of X. This construction can be generalized to an arbitrary family of functions S → X.

Symmetric to the concept of a continuous map is an open map, for which images of open sets are open. In fact, if an open map f has an inverse, that inverse is continuous, and if a continuous map g has an inverse, that inverse is open.

If a function is a bijection, then it has an inverse function. The inverse of a continuous bijection is open, but need not be continuous. If it is, this special function is called a homeomorphism. If a continuous bijection has as its domain a compact space and its codomain is Hausdorff, then it is automatically a homeomorphism.

Continuous functions between partially ordered sets

In order theory, continuity of a function between posets is Scott continuity. Let X be a complete lattice, then a function f : X → X is continuous if, for each subset Y of X, we have sup f(Y) = f(sup Y).

Continuous binary relation

A binary relation R on A is continuous if R(a, b) whenever there are sequences (ak)i and (bk)i in A which converge to a and b respectively for which R(ak, bk) for all k. Clearly, if one treats R as a characteristic function in two variables, this definition of continuous is identical to that for continuous functions.

Continuity space

A continuity space[5][6] is a generalization of metric spaces and posets, which uses the concept of quantales, and that can be used to unify the notions of metric spaces and domains.[7]

See also

- Absolute continuity

- Bounded linear operator

- Classification of discontinuities

- Coarse function

- Continuous functor

- Continuous stochastic process

- Dini continuity

- Discrete function

- Equicontinuity

- Lipschitz continuity

- Normal function

- Piecewise

- Scott continuity

- Semicontinuity

- Smooth function

- Symmetrically continuous function

- Uniform continuity

Notes

- ↑ Grabiner, Judith V. (March 1983). "Who Gave You the Epsilon? Cauchy and the Origins of Rigorous Calculus". The American Mathematical Monthly 90 (3): 185–194. doi:10.2307/2975545. http://www.maa.org/pubs/Calc_articles/ma002.pdf.

- ↑ "Heine continuity implies Cauchy continuity without the Axiom of Choice". Apronus.com. http://www.apronus.com/math/cauchyheine.htm.

- ↑ http://www.math.wisc.edu/~keisler/calc.html

- ↑ f is a function f : X → Y between two topological spaces (X,TX) and (Y,TY). That is, the function f is defined on the elements of the set X, not on the elements of the topology TX. However continuity of the function does depend on the topologies used.

- ↑ Quantales and continuity spaces, RC Flagg - Algebra Universalis, 1997

- ↑ All topologies come from generalized metrics, R Kopperman - American Mathematical Monthly, 1988

- ↑ Continuity spaces: Reconciling domains and metric spaces, B Flagg, R Kopperman - Theoretical Computer Science, 1997

References

- Visual Calculus by Lawrence S. Husch, University of Tennessee (2001)